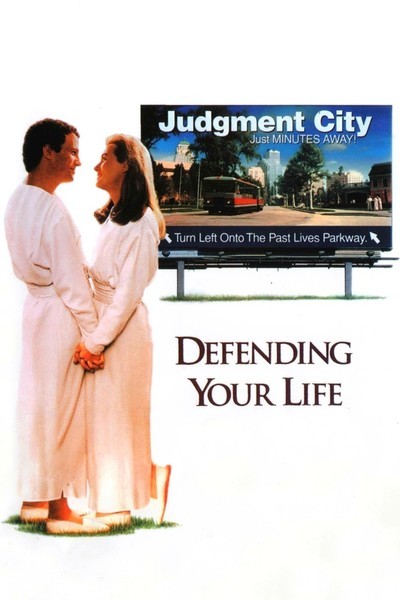

Defending Your Life

Contemplating the afterlife is a past-time that humans have endeavored with since perhaps the first moments of sympathy for the loss of a human life. The question, eternally, of where does one go when one’s life ends has been the work, almost foundationally, of religion since human records began. Defending Your Life is not trying to be religious, or even satirical, in the matter. It simply wants to consider a St. Paul at the pearly gates scenario, of what would happen if every human life had to defend itself upon its finale?

Defend itself? From what? Instinctually, we would presuppose something dark and dramatic; of humans who desperately try to self-rationalize their injustices they committed throughout their life. And yet, very meagerly, as the film centers itself upon the lead actor played by Albert Brooks (who wrote himself enviously witty lines) and his mundane issues with fear. There is no attachment of living a life, in other words, toward anything blatantly spiritual. This can be excused somewhat because of Mr. Brook’s presumably Jewish background, where there is a complete absence of salvation and hellfire needed to be stirred when one commits sin; still, it is astonishing how this subject is not even brushed against during the entire film.

It is, in other words, an appeasing popcorn faire, to an audience long past feeling a will to live. As I have remarked with such films as The Hustler, which carried such gravity about the severity and seriousness of living a life, twenty-five years later, the generation consuming Mr. Brooks’ creation does not want to ponder on the real matters in life. They want panem et circenses. It is not entirely a negative that the film is light-hearted with such a grave issue. Yet it is vital for the imagination to be able to re-create, or reinvigorate, this immortal fascination and unresolved mystery of the material ending to living and breathing. Instead we are given an alternative hypothesis which is pseudo-Oriental with its karmic explanation of the purpose of having a trial to defend one’s life. It however rubs the wrong way; as it demonstrates the futility of living a life if there is no value between the past one and the current.

But it is not a matter of concern to analyze the internal consistency of the purpose of this humorous limbo for souls that died. Is it valid, then, to criticize the film for not being serious since it is a comedy? The real challenge and deftness in being comedic is to raise such issues as the righteousness of an individual and whether or not he lived a life worth living, and his necessary defense of his life and make such a tender confrontation of reality seem as light as a feather. It could, in theory, provide a breath of fresh air, a conviction to the audience that their life is redemptive from here on out. That is to say, they could use such artwork transformatively, which as I have remarked elsewhere is the aim of all great art. Defending Your Life is shackled to the commercialism of Hollywood; yet Hollywood herself is shackled to the petulance of its movie-going consumer who refuses to seek such answers to such immortal questions, ironically when they have more time than ever to.