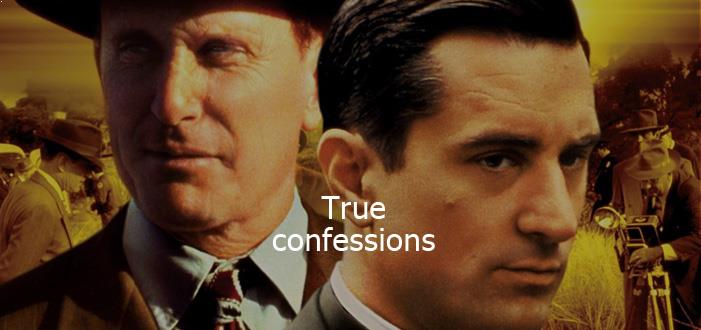

True Confessions

It’s after the war in Los Angeles. Peace time feels completely cerebral. In its vacuum of serenity, there exists the games of politics. What is striking with this vision of political tinkering is the intimate exposure to the Catholic Church and the organization of its leaders, and the necessity for the church to generate revenue from its members.

Indeed, this movie is heavily about the local church, which paints the foreground to what is really just a loose afterthought that is the Black Dahlia murder mystery. In this rendition of the mystery, the riddle is solvable by the one-time corrupt (if he still isn’t) detective or crime cop that is the brother to an up and coming rising star priest in the Catholic community.

The stardom comes primarily from his ability to handle the debts and obligations of the church by overlooking the sins of its beneficent patrons. And this is where the two intersect, whereby looking the other way can only go so far in a man’s ascent toward power. And intriguingly, the cardinal overlooking the successful management of the Catholic estate also overlooks the means in which the ends accrue. All to say, every organization that is generated by man is indeed an organic one. It is indeed subjected to the whims and mercies of human passions and conflicts. There are no men above playing the game.

And it has to be repeated how sensational it is to see the inner dynamics and tension of having such a privileged lifestyle that the priests do, and how they maintain such power over the community. The film, however, does not exercise its full artistic liberties in presuming that the Church is parasitical. Indeed the juxtaposition of crime fighter and Catholic politics is bizarre were it not for the single link that binds both narratives.

And this is a tale of two narratives. This is a tale of two brothers with similar personalities, choosing to express their abilities in completely distinct yet similar ways. They both know how to get what they want. The only difference is the setting in which it is called for.

We can’t fully consider this a noir drama simply because there are cops and murders involved. We have that lingering issue now of how the film integrates the Catholic Church into the fray. Is it to symbolize the imperfectness of man, as just enunciated with the proclamation of his organicism? Is it to critique a venerable institution for selling out, for losing its spiritual grasp on man’s reality, whereby it literally derives its sustenance from a pimp and knows it? Is this anecdote a warning shot fired before the onslaught of moral decay that Western man has been succumbing to for decades now? in other words, does the story actually fit the purpose of the narrative?

And what would that purpose be? Justice is the word that first comes to the tip of the tongue. After all, this is what crime drama’s are about. Retribution; harmonizing wrongness with righteousness. In this instance, we can clearly see the film vindicated, as the carousel of power that the priest rides comes to an end because of his negligence toward God, with the sweet irony that the downfall is caused by his incorrigible brother and his sketchy past.

With that remark, the film strikes well, making its outstanding technical performances justified.

Grade: A