Kevin Ashworth, Brittney Bertier,

Thomas Piper and Cory Washington

Photo by Jenny Graham

Kevin Ashworth, Brittney Bertier,

Thomas Piper and Cory Washington

Photo by Jenny Graham

A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay about the Death of Walt Disney by Lucas Hnath @ Odyssey Theatre Ensemble

In an irreverent and highly conceptualized play, A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay about the Death of Walt Disney by Lucas Hnath and Directed by Peter Richards at Odyssey Theatre Ensemble helps bring us into the imaginary world of a man whose imagination is his dominion. It is in the exercise of his imaginary faculties which give so many children timeless memories of joy, of play, of peace, that makes the protagonist, played exceptionally by Mr. Kevin Ashworth, seem delusional to an outward audience. And yet, that is precisely the point.

We are given, in other words, the privilege to be in a secret chamber, of Mr. Disney’s inner world, which includes his brother (played by Mr. Thomas Piper), his daughter (played by Brittney Bertier) and son-in-law (played by Cory Washington), as he plots, more or less, his fictional death. It is, one can say, the confrontation of a creative genius with his mortality, but done so in such an original setting, the effort at production by Peter Richards at The Odyssey Theatre is laudable. The ability, in other words, to facsimile the fast-paced punchiness of the dialogue with the theatrical staging, requires some originality to settle the audience into the mind of, to normal folk, a madman. But a genius one at that!

Yes – Mr. Walt Disney is creative genius par excellence. And he realizes it. He knows of his immortality – the works of Cinderella, of Pinocchio, of Snow White made animate, to preserve the heritage of the European for time immemorial. Yet is it such a bold claim to compare the man and his industry to the spirit of a Rodin? Why would there be a tinge of temerity in the proper relationship?

Because of the ostensible mass popularity of his artwork. Or rather, his productive abilities at gathering an ensemble of creative minds to produce natural magic to illuminate the minds of what must be hundreds of millions now – at scales larger than any fine artist before him has had the capability of striking so sugary sweet. Perhaps this reveals to us the wordless idea of nobility being, by its nature, rare rather than common. And that, such mundane appreciation of a smiling anthropomorphic mouse does not carry the same levity as, say, The Conversion of St. Paul by Caravaggio?

‘Conversion on the Way to Damascus’ (1601) by Caravaggio @ Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome.

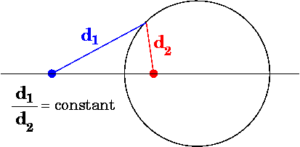

Why does fine art need to be so serious? Does this effort, in its pretension for nobility, impose a veneer upon the artists’ subjectivity in enforcing an immortal goal – that his or her artwork will stand forever? This augments further the understanding of the judgment of what is best is what is most permanent and unchanging, e.g. the Apollonian Circle.

So when we are experiencing the script of Mr. Disney, where he has the foreknowledge of his fate, which he logically crafted for himself into a legacy, the peculiarities to his grandiosity stand abruptly in contrast – even in tension – to the commonplace audience who lacks the same availability of knowledge; because they are, in comparison to his humanity, inferior in crafting immortality. Such a witness to the truth of immortal characters is in their outright eccentricities, nay, outlandishness. And yet, this is what the human civilization, as espoused by Herr Frederick Nietzsche, destines man to make! Overmen! And in droves!

Does this lead to a mercurial desire for pseudo-scientific resurrection, a la cryogenics? Certainly so! It is in the ambition to propel one towards such imaginary boundaries which is granted to those with such an unwavering determination at their goal of celebrating life and its happy mysteries. To spark wonder in the minds of little children, as illustrations do, promotes those souls to extend their vitality into the world, experience more of what is supramundane; of what only minds alone can experience as good.

Does this lead to friction with one’s own loved ones? Towards inconsideration of their feelings? Yes, it may. Or must it impose this necessary tension, on say, Mr. Disney’s daughters own subjective striving? Meanwhile, his brother Roy is there, as an Aaron to Mr. Disney’s Mosaic wanderlust, or as an obsequious yes-man who is happy to be along for the ride in constructing the Magic Kingdom?

Mr. Ashworth’s phlegmatic portrayal, his consummate poise in revealing within Walt Disney’s own inner character the realization that he cannot publicly declare himself a god among men; the tight walk with such a predicament, of being capable of willing so many minds towards his own ends, has left kings mad; the struggle to be kind and considerate yet to find relaxation in seeing one’s will accomplish its ends, at its apexes in human nature, is so modestly revealed through this staging; all through terse and wayward reflections of Mr. Disney’s own passage of his soul. It is through the wisdom of the ancients, in recognizing a permanently higher power – that of the Most High – which prepares one to continue to fulfill one’s immortal goals without being ensared by the body’s own sense of self-evident grandeur among the meekest on the Earth. This helps one, indeed, relax when confronting the possibility of death; toward knowing, in one’s honest seriousness at willing good on Earth, that the Happiest Place on Earth is becoming certainly true.