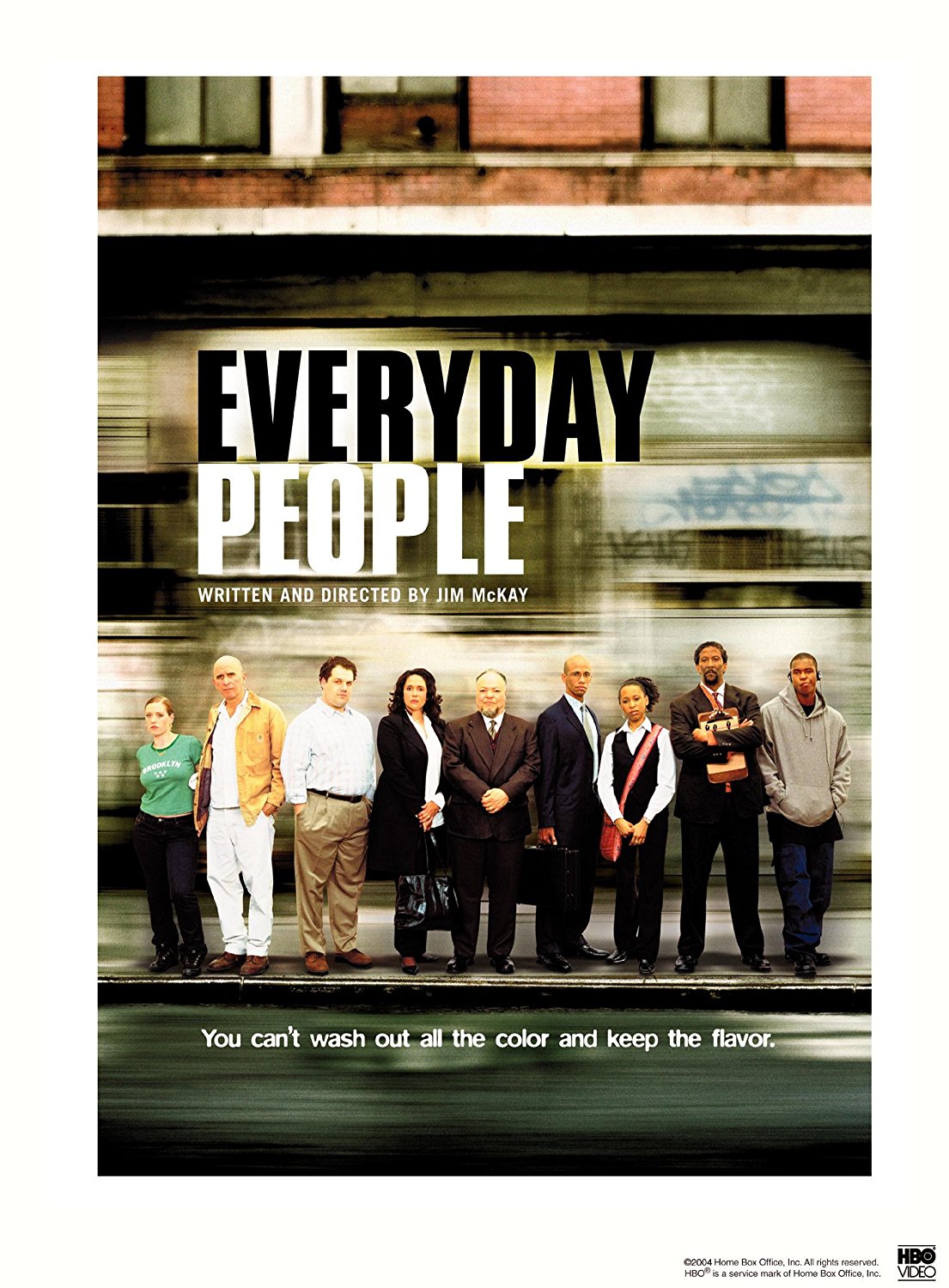

‘Everyday People’ Movie Review on HBO

Everyday People defines the “every man” as notably urban, and notably impoverished. Impoverished in the sense that if he lost his job, he would be barren. While this film was produced at the beginning of the 21st century, it is statistically precise and echoes the famed Ehrenreich Nickel and Dimed progressivist memoir of, not so much a working class, but a servile class within America. Indeed, they are a genuinely barren class who are immobile to fortune, and whose life expectancies can only worsen, not improve. While individual liberty and the protection thereof ought to preserve what an individual reaps and sows, for better or for worse, when what can be sowed cannot lead to any further human development, we have an ought right corrupted society.

Be that as it may, it is however unfair to render Caesars of this world as evil. As if being complicit in this social order they too are borne into and that is perennially out of their control unless they buy protection from the political class. Everyday People had an opportunity to paint those in the upper rungs as corrupted as such, but graciously decides not to. Yes, overwhelmingly there is an expression of the “proletariat consciousness” and their pangs and moments of grief, but we also see a glimmer of compassion within the bourgeoisie.

Realistically, though, this emotional attachment to a workforce which is being let go because of a newly inked renovation development is rare. Rational self-interest dictates business owners to act how they normally act, which is in maximizing yields and not formulating properly a contingency plan for those who have tended and cared for their property over years if not decades. Such allegiance or loyalty feudally is honorable and is the manner in which men of no means historically raised their stature. Instead now, they are discarded so carelessly for a pile of money from a banker, with the cash then stockpiled and directed by the bank sheepishly toward mediocre investment activity such as homeownership.

In some sense, Everyday People is terrific in showing a colorblind social class which universally is negatively impacted by their place of employment closing up shop. It is also poignant in its riposte to Afro-American victimization by, what would be labeled by said victims, an “Uncle Tom” who has done well for himself by buying into society and not trying to revolt against it. In fact, this character is the most fascinating to study, as he feels an inexplicable disconnection with his own ethnicity; again, a measure of genuinely how much of society is built around on an appropriately Marxian critique of the means of production rather than purely racially.

To further this critique slightly, the consciousness of the social classes towards their disposition is not necessarily deterministic as Marx wished; for such undeniable elasticity toward one’s relation towards the means of production means there is self-determination, i.e. freedom, in this relativity. It is not necessarily permanent. What does separate this successful Afro-American from the neighborhood he is an alien to, and from the restaurant employees who are subservient to market forces, must be pedagogical in nature. The imagination of boundless possibility inculcated into individuals starkly, more than ever, stratifies and rather orders mankind. This again is a reminder of how precious proper education is in society, because it is possible that all of humanity can avoid a predestined fate of being shackled to laboring for their subsistence.

Grade: C+