'Watermelon Seeds' (2020) by Summer Wheat.

Acrylic on aluminum mesh

68 x 144 inches. Copyright Summer Wheat, courtesy of the artist, Shulamit Nazarian of Los Angeles, and Kemper Contemporary Museum of Art.

'Watermelon Seeds' (2020) by Summer Wheat.

Acrylic on aluminum mesh

68 x 144 inches. Copyright Summer Wheat, courtesy of the artist, Shulamit Nazarian of Los Angeles, and Kemper Contemporary Museum of Art.

Permanent Collection @ Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art

The Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City provides a wonderful demonstration of the availability of good taste across the United States. The museum’s permanent collection gives us strong concepts of beauty, particularly of the geometrical variety, which transcend the more generic intuition of what is a beautiful image as we receive it from our experience of the civilized world. After all, though civilization is not necessary for the creation of sacred artifacts, it is in civilized life where beauty for its very sake is crafted. And it is here where the craftsmanship is positively motivated, in the majority, away from social strife and toward something more edifying. And is that not what the objective of creating beauty is? To lift spirits higher?

Are we then to suggest that spirits cannot be positively motivated with the confrontation of the truth, such as Picasso has formed for us with his two great works of the 20th century? His L’Mademoiselle D’Avingon and Guernica impose us with beautiful forms which nevertheless extend into our moral reality. As a means of sustaining disgrace? As a means of informing ourselves to act more perfectly. But what if one lacks the desire to?

How can that be? Is not acting more perfectly necessarily more beautiful? We are to suggest, then, that perfection is a form of beauty, and that beauty, being a necessary completeness of harmony – for is not love beautiful? – is an action of unity rather than divisibility between the subjective experience and the object which the mind is completely immersed in? So it is an experience of creation and not of destruction? For to gain a beautiful new experience necessarily extends the possibilities of future visibility of beauty. Destruction eliminates possibilities of goodness. Hence there is danger for an artist to be a social commentator as opposed to a pure celebrator of the good human life: of joy and gladness.

‘Genie (Pony)’ 2019 by Jiha Moon. Lithograph and screen print with nail decals on paper

Edition 4 of 30

26¾ x 21 inches

Copyright Jiha Moon, courtesy of the artist and Mindy Solomon Gallery and Kemper Contemporary Museum of Art.

So the extension of the sacred artistry of the Western Fine Arts tradition is exemplified in works like Genie (Peony), 2019 by Jiha Moon, Watermelon Seeds by Summer Wheat, and most triumphantly in the collection Della Salute / De la Salud / Of Health, 2019 by Miguel Rivera. It is this latter work which brings to bear the complexity of the human race in its desires for order yet the need to allow the permeation of chaos into its deathless experience in order to live. And if one must live, it must be toward something better than where one is now.

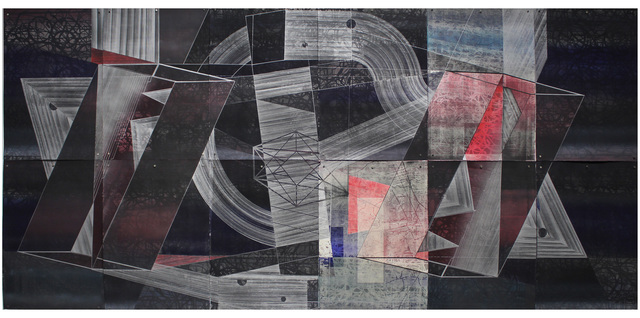

‘Della Salute/ De la Salud/ Of Health’ (2019) by Miguel Rivera.

mixed media print, drawing

80 x 168 inches.

Courtesy of the artist and Kemper Contemporary Museum of Art.

It is in this kaleidoscopic complexity of “better”, and the entanglement of control, nay, dominion, in ordering the world through the extension of the human mind which causes this unveiling of difficulty. That health is difficult to sustain? How taken for granted this is! Especially when it pertains to the brain, and how it generates thoughts, words, actions, and ultimately deeds. Though Mr. Rivera here distances ourselves from the moral plane of human acts, and instead concerns ourselves with the challenges of trying to balance the light amidst a plane of, not darkness, but ignorance. We therefore have an idea of equilibrium far removed from saccharine colors, yet also distance from black necrosis. Perhaps the idea of human vitality is genuinely this complicated for our minds to grasp. And this is what makes High Art.

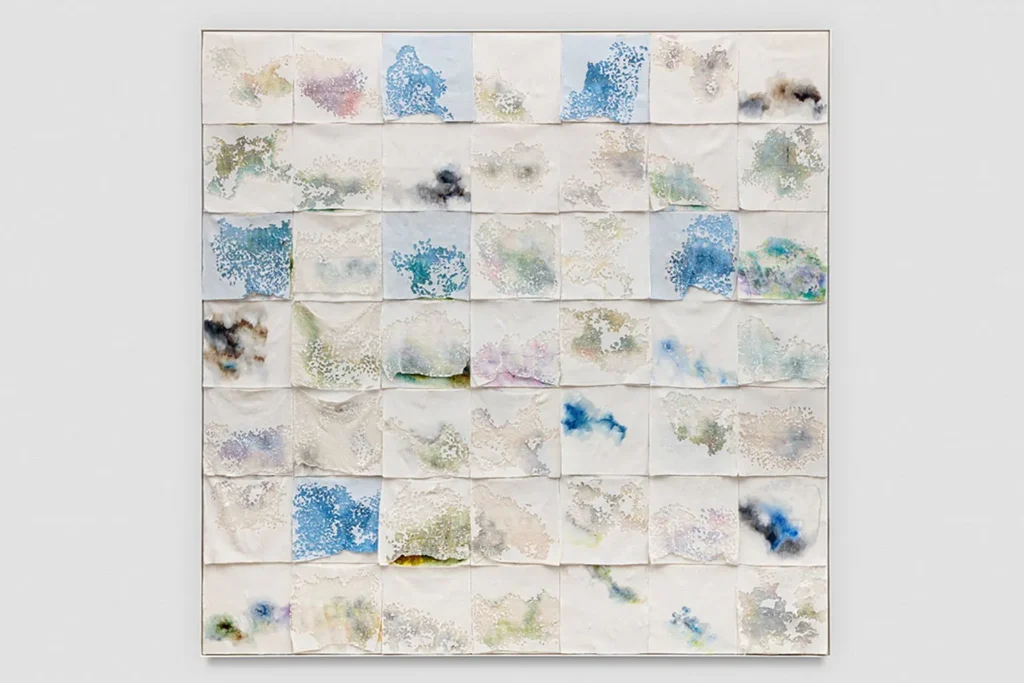

‘Noctilucent’, 2018

Liza Lou.

Oil paint on woven glass beads on canvas

97 x 97 x 3 inches

Copyright Liza Lou, courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin and Kemper Contemporary Museum of Art

Liza Lou’s Noctilucent, 2018 imposes upon us an original concept of a similar principle of beauty in human ordering, in that the simplicity is impossible to organize unto exacting perfection. The idea of coordination, as the Kemper Contemporary Museum of art exudes, is one which is beyond the naivete of a templated world of man’s ability to know it all. We therefore have a gentler extension of a pseudo cosmic-life force of the artist with an original use of virginal texture and beads. This originality is contained within every divisible, human-controlled, frame. And this is where the hidden significance of the imperfection, not blemish, of the irregularity of each fabric resides. We are here moved to think of irregularity as not necessarily in agreement with imperfection, as the uniqueness of every human fingerprint gives us the knowledge of the possibilities of a greater world with the synchronized action of all of our fates in achieving a heavenly composition. Yes, there are blots. Yes, there are tears. But it is in the efforts at coordination of agreement which makes us distinctly human. And to coordinate these agreements towards a necessarily better place than where we are now is a healthy reminder of why art is made: to be enjoyed.