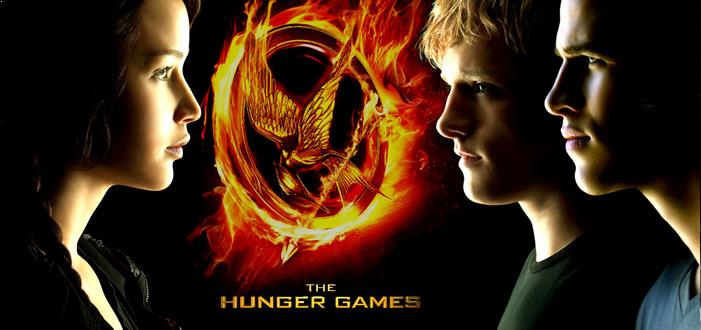

The Hunger Games

Dystopias where the world is not covered in darkness are refreshing to experience. Particularly when as part of the machination of the dystopic there is a strong stratification of society. In fact, as strong as can be: the lower castes are forced to sacrifice their children in a pagan tribute to the state.

It’s quite revealing that the power of the state is what is worshipped annually, as a reminder of the repercussions of resisting tyranny. Very frightfully, we see the entire religiosity cloaked in a bread and circus display, scintillating the decadent “Capitol”, whose citizens are unconcerned with the outright exploitation of the outer districts. The outlandish fashion and styles – intended to pique the female brain of an exotic futuristic yet alien culture – commemorate the oblivious self-indulgence; let them eat cake is a facial expression for this public, not a retort.

The narrative takes an interesting perspective, dissecting how venerated the sacrifices are – seen through their lavish living – before the clock strikes midnight. The State spares no expense, but for what purpose? To mollify the lambs before the slaughterhouse, clearly. Pacifist distortions enables the victims a complete embrace of the pageantry of the cult.

Just as we find the Romans bizarre for watching gladiatorial death sports as entertainment, we too find this society completely alien for treating the entire procession of the Hunger Games so gently. It too is entertainment. The contrast is that the Romans were aware that the players were slaves. The slaves too were aware of their place. In this society, however, we have the manipulation of social distinctions: the districts are not “slaves” are they? Are they colonies then? The propaganda does not even touch the subject, and instead supports a narrative that tells a story about how, as necessary for peace, adolescent blood must soak the ground.

The universal theme with dystopia is the dysfunction of politics. We either see an environment in the midst of such dysfunction, such as in The Hunger Games or Soylent Green, or we see one in its aftermath, such as Mad Max. Either way, the bleakness is quite a clear communique: disorder stems from the violent architecture in society.

The curious thing about the event itself is the formation of “alliances”. When the game is winner-take-all, can such a thing exist? The answer is: unlikely. In political games, like Survivor, political parties naturally form to increase the exertion of individual power over other members. Yet in a death match, there is no advantage to the strong to ally with the weak, as evidently seen. Granted, it is a plot device, but it is one that cannot exist in the game itself.

The game itself is an exercise in will-to-power. Catniss does not accomplish such vigor for life; otherwise she would not have been evading that which threatens her extinction. Conversely, she would be extinguishing the threat itself. But that would mean killing, and that would leave a character that, while does not want to harm others, must do so necessarily out of survival. This moral “quandary” of exerting strength to affirm one’s life is resolved, as one critique commented, by disabling her ability to affirm her life. In other words, the narrative depicts a reality where she must possess a strong instinct for life, yet in order to do so means she must be dominant. Coyly, she avoids this conclusion; the game resolves itself for her.

Clearly, this narrative is not for Nietzsche. And even more clearly, the fact love conquers will-to-power is the triumph of the Christian spirit, still lurking in the shadows of the Western psyche.

Grade: B+