Jacques Flechemuller @ Good Luck Art Gallery

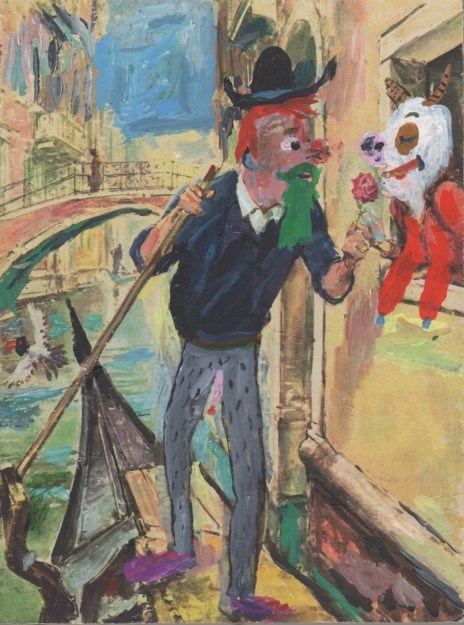

In this solo exhibition, Jacques Flechemuller defines “cheeky” for us. In which, we have the indication of humor, but something that is smarmy. It never broaches the terrain of condescension-gladly-, yet it can, because of its acidity, deliver a provocation to the subject upon perception. It does so by presenting not so much disturbing images within the playfulness, but controversial shapes and figurines of human life; instances of humanity which are very near possible but never appear on the surface, for whatever reason. We, in other words, inhabit a world just a shade above the near absurdity that Flechemuller has collected most potently in his mid-century magazine cover derivations, but we are not cognizant of such an absurdity until Flechemuller delivers it to us.

In this manner, because of the gentle revelation of the bizarreness of social convention, seen most essentially in his Je Vous Aime Beaucoup (JF66), we are left with the impression, or realization, of a world we constantly inhabit yet never actually examined as being within it. I mean here the cheekiness of a naked couple overlooking a plot of land, in one fell swoop, brings into the forefront of the subject’s mind the bizarreness of the demands for clothing. Why does this ritual even exist? No, this line of questioning does not necessarily enter into the minds of the subject, but this tension created by Flechemuller in such an intentional manner; the genuinely informal and unrefined animation of the portraiture is so far removed from the quote institutional fine arts it helps ameliorate the subject’s context of the painted moment as whimsical and not to be taken so seriously; leaves one, hopefully, with a broader more open mind to question the most obvious of things that they are grounded or conditioned within. It may be difficult to choose other compositions of everyday life to instigate such curiosity within the subject, of why things are the way they are; say for instance the convention of restaurant reservations or even seasonal holiday observances; but at the very least, an objective of moving the individual toward interrogating their world is a healthy objective for art. For such questioning of why things are done the way they are will ultimately lead to the splendor of innovation, i.e. nothing is ever set in stone. Things can indubitably be made better.

In much the same manner as treating the everyday life by ingeniously crafting cheeky embellishments upon old magazine covers, Mr. Flechmuller was practically obligated to treat religiosity in the same vein with Milking. And yet, again, wisely, we do not taste a smearing of the tiresome subject of Western Art, that being the Madonna and Child. Yes, there is some more humanity injected into the subject manner as opposed to the more sacral formulations; this is witnessed most overtly with the playing of a Mother’s bosom by the child; and yet, once more, such a reality is always underneath the surface. Is it not obvious that a human incarnation of God would suckle at the teat of his virgin mother? I.e. does not a human deity still possesses human aspects which are carnal in nature? Mr. Flechmuller, were he genuinely obscene, could have chosen a much more scatological treatment of the traditional religious subject in the West (as has been done). Clearly, then, he is not concerned with rancor and retaliation; to look downwards at society and their values, but instead to treat them in a different phasic manner, and in doing so, provide the subject with a newfound orientation toward their inhabited reality. This again, holds the promise of expanding the possibilities of what it means to be human, undeniably a positive accomplishment and the summum bonum in art.